Book Report: The Design of Everyday Things

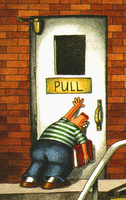

This book is for anyone who has ever pushed the pull door. One of my favorite reads in recent years, Donald Norman's The Design of Everyday Things is an entertaining analysis of why and how we are conquered by our things - alarm clocks we can't turn off, for instance, and VCRs that blink 12:00. When you turn on the wrong burner on the stove, do you (like me) call yourself a blockhead, or do you blame the design of the stove?

Norman has advanced degrees in both engineering and psychology, and he uses his expertise in these fields to describe and advocate human-centered design. He proposes that every thing can be designed so its use is intuitive and natural to our brains. If it needs a sign or a label, it is compensating. Our things should accommodate us, not the other way around. "Idiot-proofing" is just good design.

Good design incorporates error-proofing. One example of this is your computer's "are you sure?" message when you try to quit without saving. Norman describes some of the brain slips we tend to make:

capture error - when an action is captured by another familiar process

example: driving to work when you intended to go to the grocery store

description error - when an action is not defined specifically enough

example: pressing the car key remote button to open the front door of the house (I do this about once a week)

data-driven error - when data intrudes on a process

example: punching your therapist's door code into the phone to call her

associative activation error - when associations between internal thoughts generate an inappropriate action

example: calling your 4th grade teacher "Mom"

loss-of-activation error - forgetting the action at hand

example: walking to the basement and wondering what you needed from there

After reading this book, I began to notice things like door handles. Are they obvious about their push/pull status, or are they setting me up for failure? Why doesn't every state's highway system use a distinctive lane stripe for "exit-only" lanes? Why am I so attached to my Mini Cooper? The Design of Everyday Things is an eye-opener - it has caused me to hold the physical world around me to a higher standard.